Redemption in the Time of Sad Horses

A guest essay on BOJACK HORSEMAN I AM SO EXCITED ABOUT THIS

Redemption in the Time of Sad Horses

On forgiveness and Hollywood endings

(This essay contains spoilers for Netflix’s “BoJack Horseman.”)

Imagine you've written a television show about a character who is intended to be reprehensible. The supporting cast have their foibles and complexities, some of them rather larger than others, and your star character is no less complex himself, but his transgressions are an order of magnitude greater than those of the people around him. This is not a case of a flake who bails on picking you up from the airport, or a date who ghosts you the morning after a night spent together- this is a man who has crossed a moral event horizon. More than once, even.

You're careful to ensure the character stays at least marginally appealing. It's still a television show, after all, and it's important that it not turn into such an exercise in unrelenting misery that audiences no longer care to watch. No, you're committed to walking a narrow tightrope; the character must be compelling to watch, but not wholly sympathetic, and never aspirational. It must be clear that whatever ending he's headed for, it's not going to be a sitcom reset. Redemption isn't on the roadmap.

Imagine discovering that part of your viewership has taken away the opposite impression.

It’s a tricky business, writing a television show about a bad person. That kind of balancing act runs the risk of making the show more difficult to define in the eyes of viewers- especially if the ending is not an unambiguous win for the main character, who may well have gone from unlikeable to underdog. Audiences are conditioned to expect tidy resolutions that are both timely and satisfying. Nuance in television may be more true-to-life, but it’s also less broadly digestible… And it’s that specter of narrative indigestion that dogs the legacy of "BoJack Horseman," the infamous animated dramedy from Netflix.

BJH premiered in 2014, and ended its critically acclaimed six season run with a controversial series finale in early 2020. The show’s surprisingly understated conclusion remains the subject of discussion even four years on, with one of the most persistent lingering debates being whether the titular BoJack deserved the ending he got.

When it gets discussed around the Internet, BJH is sometimes branded with the cutting (though basically true) nickname of Sad Horse Show. But to say that BoJack himself is merely "sad" is underselling the character- a 90's sitcom star who has since endured a humiliating fall onto the celebrity D-list, he is a suicidally depressed, morally repugnant wreck of a horse, man, who numbs his pain with pills and booze, all the while insisting that he would change his ways and become a better person, if he only could.

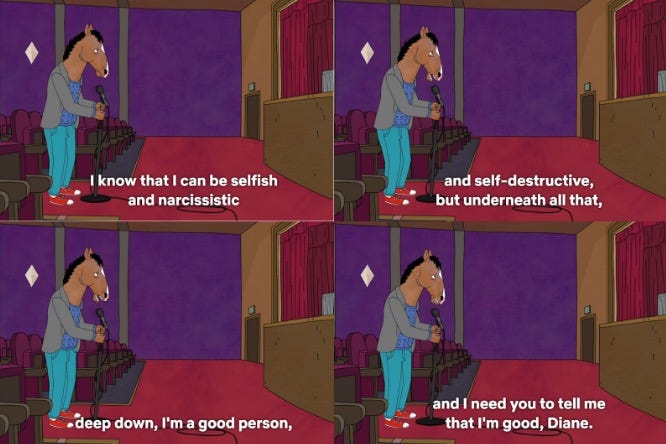

BoJack's commitment to his own self-destruction leaves a trail of collateral damage that runs through the entire series, harming almost every relationship in his life, and torching some beyond all hope of repair. Key to BoJack’s character, however, is that persistent refrain that despite the mistakes he continues to make, he genuinely wants to be better. Throughout the series, he expresses a desire to make up for past transgressions, but just can’t seem to follow through.

What eventually becomes clear is that while BoJack’s longing for redemption does seem to be sincere, he’s ultimately doomed to fail, because his impulse to apologize is rooted in a need to assuage his own guilt, rather than any genuine sense of remorse- it’s another manifestation of that same selfishness that led him to make those mistakes in the first place.

BoJack views himself as the main character around whom everyone in the world revolves, and under that line of reasoning, he longs for reconciliation on television sitcom terms, where disagreements and social faux pas of any size or intensity can be erased by an earnest conversation squeezed into the show’s closing minutes. “I did wrong, mea culpa, all is forgiven, roll credits.” Back to starting positions for next week’s episode.

It’s an attractive fantasy to BoJack in particular, because it implies that the act of apologizing is enough to completely undo the damage a relationship might sustain, without any need of self-examination or lingering guilt. However, life does not operate on sitcom logic, and despite the circumstances of BoJack’s life continually reinforcing this immutable fact, he doesn’t seem to truly internalize it until the very end.

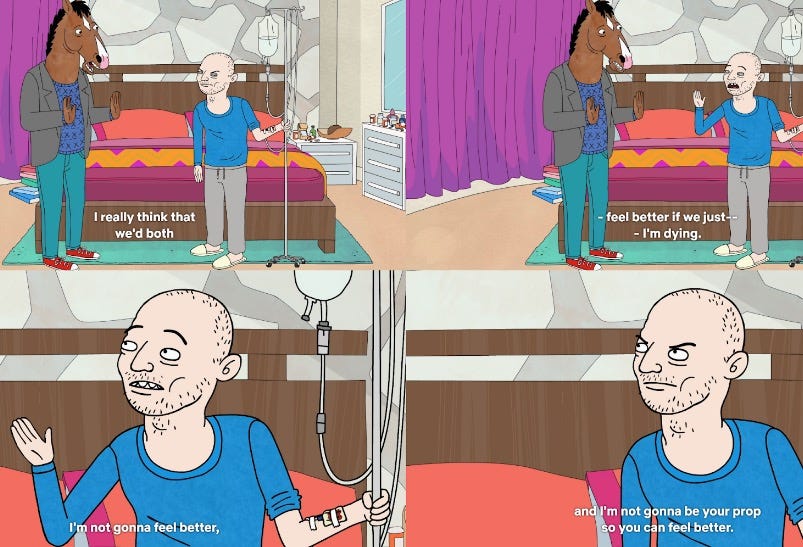

Gradually, then with steadily rising volume, the show builds on the idea that when you do great harm to someone, the person you’ve hurt isn’t obligated to forgive you. It’s BoJack’s former friend Herb Kazazz, dying of cancer and long out of BoJack’s life until this last meeting, who first delivers that thesis statement near the end of the first season, a crushing verbal sledgehammer blow that leaves BoJack reeling.

BoJack is forced to self-examine and acknowledge that his motivation was insincere from the start: he didn’t apologize to Herb because he genuinely wanted to express remorse for betraying his friend and mentor, he did it because he wanted closure for himself. Specifically, closure of the primetime variety- the main character, humbled and changed for the better, earns the deathbed forgiveness of the person he’s hurt the worst, and is thus granted absolution in perpituity, along with the freedom to never think about his own wrongdoing ever again.

But Herb knows BoJack better than almost anyone- he knows the kind of man BoJack really is, and he refuses to let him continue to play the role of the cross-toting martyr.

It’s the last time BoJack sees Herb Kazazz. The door to reconciliation hasn’t just been slammed shut- it’s been paved over entirely. Turns out the door hasn’t been there for years.

The rejection sends BoJack spinning just long enough to retreat into the velvety black oblivion of drugs and alcohol. One harrowingly exaggerated bender later, followed by a somber vow to get serious about fixing his life, and he’s ready to reset for the end of season one.

Roll credits. Back to starting positions. He imagines he’s learned something from the experience.

He hasn’t. In his mind, it’s still all about him, and that means he’s doomed to make the same mistake for five more seasons, until at long last, at the very end, he begins to grasp the concept that if you want to make things right, you have to center the feelings of the person you’ve hurt, not your own. That’s harder to do than it sounds, because it might very well mean accepting that the person you’re apologizing to does not forgive you, and doesn’t want you in their life anymore.

That’s the scenario BoJack finds himself in when the series concludes. He’s put everyone around him through hell by this point, to say nothing of the beating he’s taken himself, with the combined weight of it all having shaken him so profoundly that he’s actually loosened his grip on his ego. While BoJack forgoing his usual “Plausibly Young Male Lead” jet black dye job to embrace the natural graying of his hair might signify that he hasn’t yet completely given up on sitcom logic (characters going through big changes always change their hair!), it’s clear that he has finally begun to change for the better.

He still has friends, but they’ve put up barriers- for the sake of their own happiness, boundaries have been established. It’s clear that things won’t be the same going forward. In some cases, it’s implied that the battered friendship will continue to fade until nothing remains, that quietly devastating interpersonal Irish Goodbye that we’re all familiar with.

BoJack is aware of all of this, and he’s not fighting it. He’s not the main character demanding the heartwarming forgiveness that the script tells him he deserves- he’s a human being who has to live with knowing what his selfishness has cost him in the past. He’s just a horse, trying to be a good man.

The ending of BJH was controversial because it was assumed that there were only two ways the show could end: forgiveness, or destruction. One of the longest running theories prior to the show’s conclusion was that if the show didn’t end in redemption for BoJack, then surely it was going to end in his suicide- and to be clear, the harrowing penultimate episode, “The View From Halfway Down”, danced with this dark possibility.

There was always a third option, however, and the nuance of that third possibility is where the heart of BJH really lives: the prospect of BoJack taking ownership of his transgressions, and living with the consequences. This is the outcome BoJack refused to consider for a very long time, so it comes as a bit of a surprise that he manages to get there, against all odds. This subversion of expectation is summarized quite succinctly in the show’s closing conversation between BoJack and Diane.

Diane Nguyen is a relative newcomer in BoJack’s life, having been hired to write his autobiography in season one- though it is later revealed that they actually met for the first time years prior, a meeting that BoJack, characteristically, does not initially remember. Over the course of the series, she becomes a friend, a confidant… And the latest in a long list of women he has victimized.

BoJack’s fraught relationship with women- his difficulty with viewing them as anything other than sexual prospects, emotional janitors, or adversaries- is the rotten foundation that his friendship with Diane is built upon, and she cycles through all three archetypes in BoJack’s perception as he struggles to change. Their dynamic very gradually moves toward something resembling a normal friendship as they both grow and change, but it never fully equalizes emotionally, and Diane eventually realizes that BoJack’s outsize dependence on her is alienating her from the rest of her life.

When her breaking point arrives and the distancing barriers go up, she frames the situation with more grace than most would be able to give in such a challenging moment. Not surprising, really, she is a writer.

Diane’s decision to distance herself serves as the closing argument in BJH’s suggestion that the idea of redemption as sold to us by movies and television is almost wholly fictional- an oversimplified binary that doesn’t reflect just how complex human relationship dynamics often become. There are no easy answers, no quick solutions, and redemption doesn’t come cheaply- if it comes at all.

The real price of redemption isn’t a few minutes of uncomfortable conversation and performative contrition- it’s a lifetime of accountability. It’s accepting that even if you feel genuine remorse for what you’ve done, you can't un-inflict the damage, and the only way to really make it right is to let the injured party set the terms. It’s letting any pain you might feel from the experience inform your actions going forward, and shape you into a better, more emotionally aware person.

It’s not a neat and tidy ending. That’s the nuance of living, though- part and parcel of the human condition is that we don’t often get the exact endings we want. As a matter of strict fact, we rarely get clearly defined endings at all, but for that big series finale that’s waiting for all of us at the end of this mortal coil. But that’s all the more reason to keep going, to keep getting better and better with time. As a wise jogging baboon once told BoJack, “It gets easier. Every day, it gets a little easier. But you gotta do it everyday. That's the hard part. But it does get easier.”

(He/Him), an appreciator of film, television, literature, animation, and Monte Cristo sandwiches. Seeking clarity through observation and critique of pop culture. A student of the art of altercation. Observations and insights can be found on on Bluesky at @quartercirclejab.bsky.social, on TikTok at @quartercirclejab, or (Tara hopes) with more written work at .

Wow, that was a great essay.

Is "emotional janitor" specifically mentioned in the show? I really love it